How to Convince People to Stop Smoking

As illustrated by the following picture, I used to smoke cigarettes. In fact, I used to smoke a lot of cigarettes, I was a heavy smoker by most standards: about a pack and a half a day. Anyway, as indicated by the use of the past tense, as well as the “🚭” emoji featured in the navigation bar, I’m past smoking! It’s been 111 days since I last smoked a cigarette. This is a short essay on my experience as an ex-smoker and what ultimately pushed me to quit.

I started smoking when I was 16 years old. Anyone who says they enjoyed the first time they smoked a cigarette is lying, but at the time I was very uncomfortable with the fact that I looked younger than I was, and I (unconsciously) felt like cigarettes would help me look older — as they say in Cidade de Deus: “Eu fumo. Eu chero. Já matei. Já roubei. Sou sujeito homem.” Over time I started smoking more and more, menthol cigarettes gave way to red filter cigarettes, until “being a heavy smoker” became part of my identity.

I distinctly remember an episode, I was about 13 years old, when I though to myself: “Why on god’s green earth would anyone on their right mind smoke a cigarette knowing how harmful it is?”. Nevertheless, three years later I found myself smoking 20 cigarettes a day. This is because, of course, smoking as a habit is not a conscious decision. Becoming a heavy smoker is usually a very gradual process, the product of an uncountable number of tiny decisions. No one wakes up one morning screaming “I will start smoking today! This is a great idea!”

This is what I think most anti-tobacco propaganda gets wrong: no one chooses to be a smoker, so aggressively telling people how harmful of a habit smoking is is not an effective way of preventing them from doing so. In fact, I used to feel a lot of hostility towards anti-tobacco propaganda because of this reason. I was distinctly aware of the harmful effects of tobacco consumption, so the numerous attempts to shock me with this information sounded like an insult to me. Did people really think I didn’t already know cigarettes are bad?

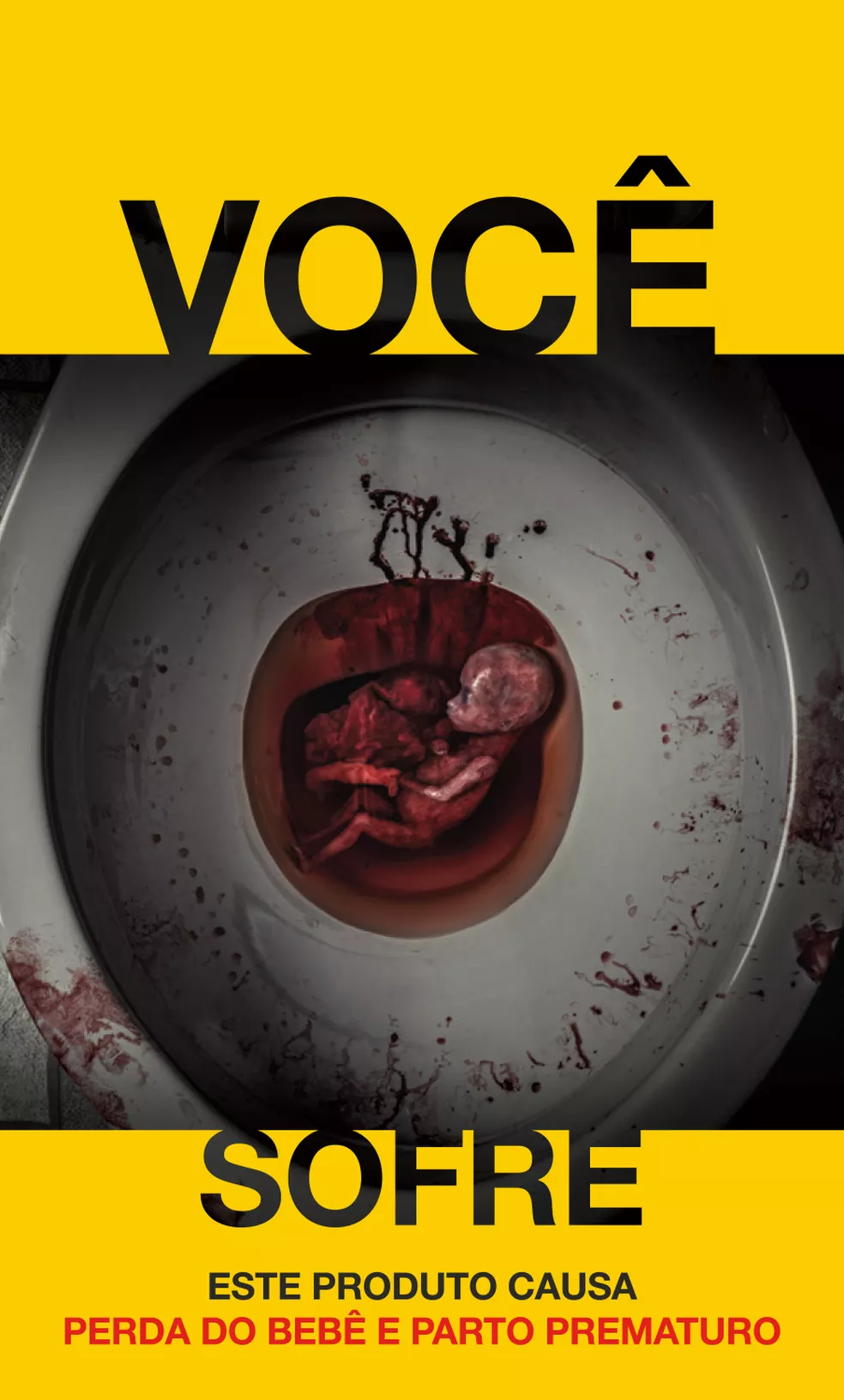

The grotesque imagery displayed on the back of cigarette packs — if I had to pick a favorite, I would certainly go for the picture of a bleeding red fetus inside a white porcelain toilet — is a great example of this: the aggressiveness of it made me feel attacked. Instead, I argue that we should treat smokers — a.k.a. potential ex-smokers — with compassion, as this is the strategy that ultimately pushed me to quit after 6 years of smoking.

More precisely, what convinced me to consider quitting was the Ciência Suja podcast episode on the tobacco industry, entitled “Cigarette: the father of modern science denial” — if you happen to speak Portuguese, I strongly recommend listening to this episode. There are a number of reasons why this particular episode managed to cut through my hostility towards anti-tobacco propaganda. First of all, the episode heavily features the testimony a laryngeal cancer survivor named Ricardo Gama.

I can’t really grasp why, but for some reason I was much more sympathetic towards the voice of an ex-smoker. This is perhaps the primary reason why this specific piece of propaganda was so effective to me: the fact that the cautionary tale of a cancer survivor was told by the survivor himself made it feel like the warm words of a friend who understood me. Ricardo described how he started smoking when he was about 17 years old — which was, of course, very relatable to me — and how he quit when he was 26 years old, after about 10 years.

He then described how he was diagnosed with laryngeal cancer when he was 41, and how the subsequent removal of his larynx — a procedure known as larygectomy — affected his everyday life. This ties up into the next reason why I was convinced: I used to fool myself with the though that smoking wasn’t that risky if I were to quit early on. Unfortunately for him, Ricardo proved this is clearly not the case. I was also profoundly moved by the segment at the start of the episode on the Sua Voz choir, a choir formed by larygectomy patients such as Ricardo himself.

I guess what I’m trying to get at is I think that switching the perspective from “you, the smoker” to “we, the smokers/ex-smokers” may lead to an increase in the effectiveness of anti-tobacco propaganda. Again, this opinion is entirely based on my personal experience, which is anecdotal evidence. I’m actually very curious to know whether or not there are rigorous studies that investigate this hypothesis, please let me know if you know some! Either way, I’m hoping this article can provide some insight on anti-tobacco propaganda from the perspective of an ex-smoker.

I guess this is all I had to say. See you later 😛